![]()

![]()

![]()

Third Branch of Life Bares Its Genes

By John Travis

|

For eons, the methane-belching microorganisms lived anonymously on the

floor of the |

|

Beyond answering questions of basic biology, these novel microbial genes

may inspire practical spin-offs, such as industrial enzymes that work at high

temperatures or genetically engineered organisms that make methane, an alternative

to fossil fuels.

The newly identified genes should also help unravel the mystery of the

Archaea. This group of microscopic organisms, which includes M. jannaschii,

shares similarities with bacteria but may be more closely related to plants and

animals, say some scientists.

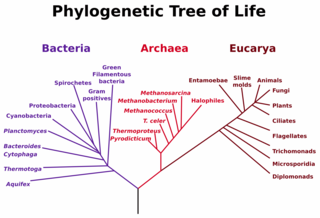

Until recently, biologists had divided the so-called tree of life into

two main branches, the Bacteria (or Prokaryotes), and the Eucarya (or

Eukaryotes). Among other dissimilarities, eucarya, which include fungi, plants,

and animals, house their DNA in an intracellular sac called the nucleus while

bacteria do not.

In 1977, Carl R. Woese of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

shook this tree of life when he declared that several known microorganisms

deserve a branch of their own (SN: 11/12/77, p. 310). The microbes, originally

labeled archaebacteria by Woese and now called archaea, do not have nuclei but

differ significantly from most bacteria in many other ways.

Scientists initially found archaea only in extreme environments such as

the hydrothermal vents, the

Over the last few years, Venter and his TIGR colleagues have pioneered a

novel strategy to quickly sequence genomes and have proved the method effective

with the sequencing of the first two bacterial genomes (SN: 6/10/95, p. 367).

In essence, they randomly chop an organism's strands of DNA into thousands of

small fragments whose sequences can be quickly read. With computer software

that recognizes overlapping sequences among the fragments, the researchers then

piece together the complete genome.

Applying this strategy to M. jannaschii revealed 1,738 putative

genes, only 44 percent of which resemble genes from other organisms, report

Carol J. Bult of TIGR, Venter, Woese, and their colleagues in the Aug. 23

Science.

The genes presumed to play a role in M. jannaschii's metabolism

largely resemble bacterial genes. Those genes greatly interest investigators

because M. jannaschii is the first autotroph whose genome has been

sequenced.

Autotrophs, unlike animals, do not depend upon amino acids and organic

molecules from their environment. M. jannaschii "makes everything

it needs from carbon dioxide, nitrogen, and hydrogen," says Venter.

Understanding how and when autotrophs evolved may topple the popular

idea that life originated in a primordial pool rich in amino acids and organic

molecules. "That theory has been challenged, especially in recent years,

by scientists, including myself, who believe life began in an autotrophic

way," says Woese.

While M. jannaschii's metabolic genes mirror those of bacteria,

other of its genes match those of eucarya. Proteins from these genes appear to

translate DNA into RNA, assemble proteins, and copy the microbial DNA.

This initial look at M. jannaschii's genome seems to support

Woese's long-held theory that archaea are more closely related to eucarya than

to bacteria. Yet some investigators caution that a definitive conclusion will

demand a much more rigorous genome analysis and the sequencing of other

genomes.

"Until now, we've been making huge extrapolations from minimal

data. The picture won't be complete from a small sampling of genomes, however.

It is going to require 50 to 100 genomes, of organisms that are widely

distributed throughout the universal tree of life, to really have a sense of

what happened in our evolutionary history," says Mitch Sogin of the Marine

Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Mass.

For example, Woese expects the sequencing of a second archaea genome,

scheduled for completion this year, to allow scientists to discern how many of

the novel genes in this first genome are shared by other archaea.