Waste Products of Nitrogen Metabolism

|

|

|

Proteins

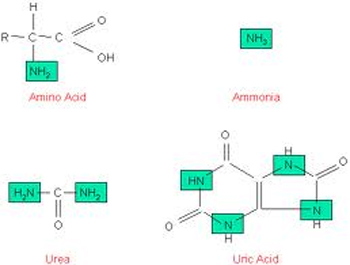

and nucleic acids are the two main sources of nitrogenous wastes. Proteins are the source of over 95% of the

total amount of excreted nitrogen; nucleic acids make up the remaining 5%. The major problem is to get rid of the

ammonia (NH3) that forms when amino groups (–NH2) are

removed from amino acids during protein catabolism. Because ammonia is a very toxic molecule, it

is kept in low concentrations. In the

blood of vertebrates the range is 0.0001 to 0.003 mg/100 ml. Higher

concentrations can be lethal; for

example, a mouse will die if the ammonia concentration in its blood reaches 5

mg/100 ml.

Some

animals excrete nitrogenous wastes directly as ammonia, but many species

convert it to urea or uric acid immediately after it forms. These compounds are much less toxic which

permits them to be transported and stored until they can be excreted. The

animals that excrete nitrogenous wastes as ammonia need access to lots of

water; therefore, ammonia excretion is most common in aquatic species. Because ammonia molecules are small, they

easily pass through membranes and are lost by diffusion to the surrounding

water. In many invertebrates, ammonia

release occurs across the whole body surface. Teleost (bony) fishes excrete almost all of their nitrogen as ammonia

through the gills and in the urine. Excretion of most of the nitrogen as ammonia is called ammonotelic

excretion.

|

In

a third category are animals that, because of their dry habitats (or some other

reason requiring water conservation), excrete a minimal amount of urine that

contains little or no water. These

animals (e.g., land snails, insects, birds, some frogs and many reptiles)

convert ammonia to uric acid. Unlike

ammonia or urea, uric acid is insoluble in water, so only small amounts are

retained in solution–greatly limiting their toxicity. (For any substance to be toxic and achieve a

biological effect, it must be in solution.) Excretion of nitrogen in the form of uric acid is called uricotelic

excretion. Most uricotelic animals

excrete their nitrogenous waste as solid or semi-solid urine, or as uric acid

crystals.

Ammonia,

urea and uric acid are the most common nitrogenous waste products, but not the

only ones. Some sharks secrete

trimethylamine oxide (TMO). A variety of

animals also excrete small quantities of creatine and creatinine. Some animals even wastefully excrete some of

their excess amino acids.

Because

urea, uric acid and TMO are less toxic than ammonia, why don’t more animals

excrete most of their nitrogen in these forms? The answer can be explained as “biological economics”. The synthesis of these compounds is

energetically costly. Nearly half of the

food energy a terrestrial insect consumes may be used to process metabolic

wastes! In aquatic insects, ammonia

simply diffuses out of the body into the surrounding water. In general, an animal excretes its nitrogen

in a form requiring the least expenditure of energy, given the environment in

which it lives.

A

few animals excrete nitrogen that comes from the metabolism of purines (e.g.,

adenine and guanine). Purines can be

broken down to ammonia only if the animal has the specific enzymes. Most animals excrete purine nitrogen as uric

acid or as one or more intermediate products.

|

|